Mobile Navigation

- Out Professionals

- Home

- Events

- Out Pro Ed

-

News

News

- 7 Revealing Findings from a First-of-Its-Kind Map and Analysis of American LGBTQ Bars

- People Who Think the Gay Community Isn’t Also Under Threat Are Naive. Here’s Why.

- Trump’s Harvard Attacks, White Men and DEI

-

Is WorldPride DC Safe in Trump’s America? The Director of Security Weighs in

-

Why We Should Always Call Attacks on LGBTQ People ‘Human Rights Abuses’

As WorldPride DC Begins, A Look Back at the Eight Cities that Led the Way

WorldPride DC, which is expected to bring as many as 3 million visitors and $700 million to the city’s economy, began on May 17 and will culminate on June 8 with a march.

This is the ninth WorldPride and has already garnered controversy as it takes place in America’s capital city, where the Trump administration has dismantled LGBTQ rights and made relentless attacks against the queer community. Many countries have issued travel advisories for trans people visiting the U.S., and WorldPride organizers have cautioned international trans folks from attending. Despite this, hundreds of thousands of people will celebrate and protest over the next two weeks.

The eight WorldPride events that have taken place over the last 25 years have all included challenges and triumphs. Here’s a look at each of them through the lens of attendees who experienced it.

The first WorldPride was held in Rome, the capital of Italy and home of the Vatican. The location was important: Italy was—and still is—among the weakest countries in Western Europe for LGBTQ rights, with gay marriage and non-binary gender markers still unrecognized today.

The weeklong Pride was held in July during the Catholic Church’s Great Jubilee. Pope John Paul II was outraged, calling it an “offence to the Christian values of a city that is so dear to the hearts of Catholics throughout the world” and adding that homosexual attendees are “intrinsically disordered.” The Vatican even convinced the city government to withdraw its promise of $200,000 in financial support for the event. While the money was eventually returned due to backlash, the city still removed all of its official branding.

Despite this, the event was a huge success.

“It was beautiful,” Renato Sabbadini, who helped organize the event, told Uncloseted Media.

Sabbadini, who was in his twenties when he helped organize the event, says that while previous Rome Prides drew 10,000-20,000 people, WorldPride brought in 700,000 people—so many that they couldn’t all fit into the march’s destination, the ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium known as Circo Massimo.

Sabbadini was a board member for the Italian LGBTQ rights group Arcigay and had helped draft the initial proposal for WorldPride. He was proud of what his work accomplished, both in size and in impact. He was most emotional seeing the sheer number of non-LGBTQ people who turned up to show that Italy was ready for change.

“The Italian population, for the first time, wanted somehow to assert the fact that Italy was no longer a country that could be considered simply as a sort of colony of the Vatican, but it was a secular country with its own consciousness and values,” Sabbadini says.

Six years later, the second WorldPride was held in Jerusalem. The location—a holy site for Judaism, Christianity and Islam—was once again chosen by WorldPride’s international and official organizers to protest religious and state discrimination against the LGBTQ community. The region was also a controversial choice.

While Israel is seen as the most progressive country for LGBTQ rights in this region, the Middle East is still home to many hostile countries, including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen, where you can be killed if found engaging in “homosexual acts.”

The march was postponed twice, first due to Israel’s 2005 disengagement from Gaza and later because of the 2006 Israel-Lebanon War. Leaders of all three major Abrahamic religions opposed the event, saying that it would create the impression that homosexuality is acceptable. “They are creating a deep and terrible sorrow that is unbearable,” Shlomo Amar, Israel’s Sephardic chief rabbi, said in a news conference.

Abdel Aziz Bukhari, a Sufi sheik, added, “We can’t permit anybody to come and make the Holy City dirty. This is very ugly and very nasty to have these people come to Jerusalem.”

While the event eventually took place in November, it was boycotted by many LGBTQ rights organizations in protest of Israel’s occupation in Palestine and invasion of Lebanon.

Deeg Gold, a boycott organizer, says that the attention garnered by the boycott helped spread awareness about LGBTQ Palestinians and pro-Palestinian activism. They say it also helped popularize the term “pinkwashing,” which is now frequently used to describe the practice of using LGBTQ-friendly aesthetics for profit without actually supporting the community.

“It brought, for the first time, an international awareness that there are a lot of queers in Palestine.”

At London’s WorldPride in 2012, the global LGBTQ community was still facing significant legal and social challenges. 40% of UN Member States still criminalized same-sex sexual acts. The event, which featured a march with 25,000 participants, aimed to confront these injustices by celebrating progress and highlighting the work still left to do.

The event also opened new doors for inclusivity, including for 42-year-old mathematician Michael Doré, who organized the first-ever Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) Conference.

“There have been attempts before at having big events, but WorldPride really [made it happen],” Doré told Uncloseted Media.

The one-day conference brought together roughly 100 attendees from across the globe and included a keynote titled “Asexuality BC (Before Cake),” which traced the early development of the asexual (ACE) movement and highlighted the intersections between asexuality and non-binary identities.

“The usual argument is that ACEs are not really oppressed,” says Doré. “ACE is just about not wanting to have sex or not wanting a relationship. I disagree with it. A lot of what ACEs go through is actually similar to the wider LGBTQ movement … [such as] feeling broken and feeling the orientation is not going to live up to other people’s expectations.”

Doré says the conference was “just extraordinary.”

She hugged the other organizer and said, “You are the first other asexual person I’ve met in my life!”

“She was so excited to be there, and said it was the one day in her life she felt she could be herself.”

Building off the momentum from London, WorldPride returned just two years later to Toronto, which is seen as one of the most LGBTQ-friendly cities in the world. It’s also the largest city in Canada, one of the strongest countries in the world for LGBTQ rights.

Kalyn Heffernan, the 38-year-old frontwoman for the queer and disabled hip-hop group Wheelchair Sports Camp, performed at the march alongside Tangled Arts, an organization that promotes disabled artists.

“It was a big deal to … get to play at WorldPride in Toronto—pretty amazing,” Heffernan told Uncloseted Media.

Heffernan lives with Osteogenesis Imperfecta, a disease where bones break easily. She actively advocates for queer disabled folks—who, she notes, were integral to the origins of Pride. She says the fight for LGBTQ rights must also include accessibility, intersectionality and justice for all bodies and identities.

She adds that she doesn’t feel like Pride represents the disabled community like it has in the past, in part because of all “the corporate backing.”

While Heffernan had some mixed feelings about Toronto’s WorldPride, like for the large police presence at the march—which she finds “antithetical” to the LGBTQ movement’s radical history—she says she was grateful for the opportunity and for what Pride represents, especially as LGBTQ rights continue to be under attack.

Three years later, under the banner of “Viva la Vida,” or “Live Life” for non-Spanish speakers, WorldPride Madrid brought an estimated 3 million people into the heart of Chueca, the city’s historic LGBTQ neighborhood.

From early grassroots activism to becoming one of the first countries to legalize same-sex marriage in 2005, Spain has emerged as one of the world’s most progressive nations when it comes to LGBTQ rights.

“It was a very fun, very cool environment,” says Justin Seymour, a straight man and staunch ally from Lafayette, Indiana.

Seymour, who was in Spain to visit his then-partner’s family, says his first Pride experience was unexpectedly welcoming. “One guy I spoke with was like, ‘Oh, you’re straight?’ and I was like, ‘Yeah.’ And he goes, ‘Well, that’s too bad.’ So, I felt very welcome.”

What stood out to him most was the atmosphere of inclusivity, one that he had never seen in his conservative hometown. “There were small details. … They changed the lights to be two women walking. That was totally unnecessary but very cool,” he says. “One of the major buildings in Madrid had the pride flag draped over it. Everybody seemed really supportive and [to be] having a good time.”

He says that straight people have something to learn from Pride.

Seymour also thinks straight people should embrace any discomfort they feel around Pride. “Being a straight white guy, you kind of get to do whatever you want. You’re welcome anywhere,” he says. “Being in the minority, that’s not normal [for us] and can be uncomfortable. But it’s important to lean into.”

Seymour recommends that everyone go to Pride. “Getting a little uncomfortable and trying to get to know people and ask questions is crucial,” he says, referring to the fact that studies show how interacting with members of different groups can reduce prejudice and lead to more empathy and understanding. “It’s educating yourself. It’s a good way of getting rid of your ignorance, and getting familiar with the community in and of itself.”

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, WorldPride 2019 took place in New York City.

The 1969 riots were a notable turning point for LGBTQ rights. They began as a protest in response to police raids at the Stonewall Inn, a historic gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village. One year later, the first Pride marches would be held in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago to commemorate the riots.

Due to the grassroots nature of the riots, the commercialization of WorldPride was a source of tension. As a result, the Reclaim Pride Coalition organized the Queer Liberation March, an alternative Pride that rejected corporate sponsorship and police presence. While the Queer Liberation March was initially made up of 8,000 people, it grew to 45,000 that same day.

Stacy Lentz, the co-owner of The Stonewall Inn, says WorldPride’s “energy and emotion was one of resilience.”

Lentz, a lesbian originally from Kansas, says that many attendees were touched by the event’s historical significance.

“There was so much unity,” she says. “There was everyone together, everyone celebrating, millions of people. … The city was just electrified that year.”

Lentz says the energy inside Stonewall was palpable. “We had Taylor Swift come and perform at the bar, singing ‘Shake It Off’ with Jesse Tyler Ferguson. … I joked that I couldn’t even get into my own bar that weekend.”

Flash forward two years to Copenhagen and Malmö’s joint Pride in 2021. The theme, “#YouAreIncluded,” took place in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and emphasized human rights for all people, regardless of “sexuality, gender identity, race, religion, appearance, economic status, nationality, refugee status, health, HIV status—or any other factor.”

Video courtesy of Yates.

“Copenhagen really rolled out the red carpet for Pride. I’ve never seen so many rainbow flags in my life,” Victor Yates, a writer and educator, told Uncloseted Media. “Not only did I feel safe, but I felt welcomed to the city. It was such a beautiful experience because even people who weren’t participating in Pride wanted to experience what was happening.”

Denmark is recognized as one of the most LGBTQ-friendly countries on earth and was the first to grant the right for same-sex couples to enter into registered partnerships in 1989.

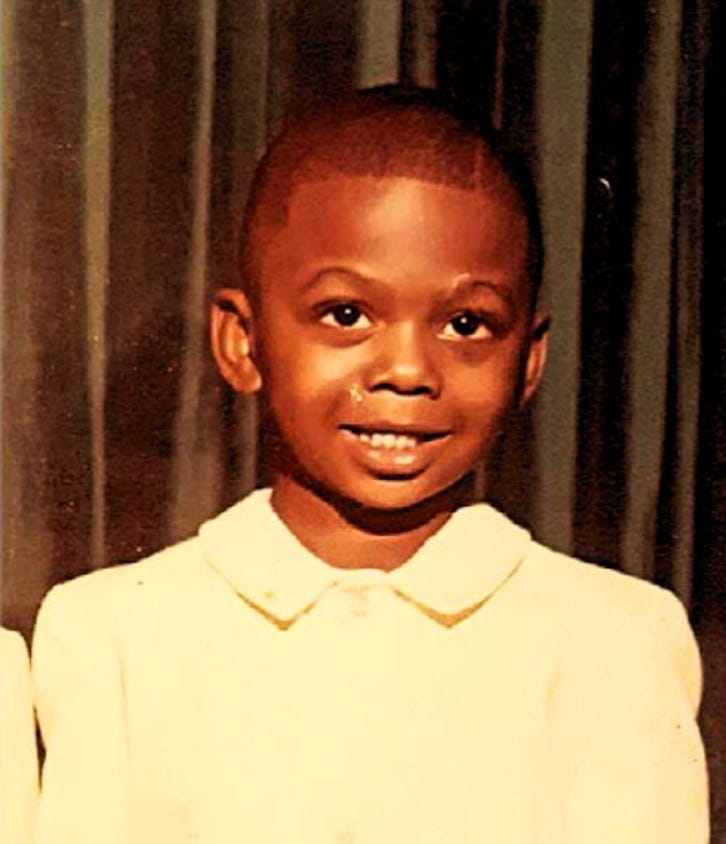

Yates, a Black gay man, grew up in Florida, where he was afraid of attending Pride events. “In Jacksonville, I never saw representations of positive queer images. There were always billboards about not having an abortion and that being gay is a sin. … And because of this, I grew up not wanting to attend Pride events.”

He remembers riding the bus in the early 2000s and passing a Pride event in the park. “The bus driver commented, ‘Where’s the police when you need them?’ And it just took me aback,” he says. “This isn’t the 60s, this isn’t the 50s. We’re living in a modern time where we have modern ideas, but there are still some people who believe that queer people should be arrested for just living their life authentically.”

Video courtesy of Yates.

Yates’ experience in Copenhagen transformed his understanding of what Pride could be. “I was like, ‘This is magical,’” he says.

Video courtesy of Yates.

Yates says part of the unity he felt was because of the planning that went into the event.

“There were active conversations about how to welcome people to Copenhagen Pride. And I felt like every building, every organization, participated. Every encounter that I had with someone who was local was pleasant. I didn’t feel othered while I was there.”

In 2023, Sydney, Australia hosted WorldPride, after the country released a “rainbow birth certificate” in 2022, where citizens could opt to not list their gender.

But despite these political advances, there was controversy around high ticket prices, with the Sydney WorldPride organization receiving backlash for the whopping $1,497 they charged for three-day passes.

Alan Maurice, a South-Asian gay man living in Sydney, has fond memories of marching across the Sydney Harbor Bridge. “We don’t often get an opportunity here in Sydney to close off a main artery and turn it into this big rainbow march,” he told Uncloseted Media. “There were queers and allies and all kinds of people went and crossed. And so that was a wonderful feeling.”

Though Maurice enjoyed his time at WorldPride, he felt there was a lack of South-Asian representation at the event. “The Indian subcontinent’s got billions of people, so there’s a pretty large percentage of queer people. Not a single person was invited to present or speak during the Human Rights part of it … so that was really disappointing,” he says. Despite this, Maurice left WorldPride feeling the event had strengthened the LGBTQ community.

Additional reporting by Soph Kristen and Nico DiAlessandro.

Fact-checking by Amanda Donndelinger.

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

Out Professionals is a 501(c)(7) nonprofit social organization in the USA. • EIN 13-3918457

OutProEd (Out Professionals Educational Foundation, Inc) is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit. • EIN 87-3853989 • Donations are tax-deductible.